Knock knock.

Who’s there?

The police. You posted something on social media nine months ago, and someone has taken offence. These five other officers are here to escort you to the station for an interview.

Not a terribly funny joke, I’ll admit. In fact, it isn’t a joke at all, but reality in Britain in 2025. The country that gave the world liberal democracy and the foundational texts on freedom of speech now dispatches a police squad to your nan’s bungalow because she commented “we’re full” on Facebook beneath an article about immigration.

I exaggerate but only slightly. The Times reports that Britain’s police are making 30 arrests a day for “offensive posts on social media and other platforms”. That’s 11,000 arrests per year. For writing words. The knife-crime epidemic will have to wait, presumably.

Britain’s descent into unreason takes many forms – immigration chaos, economic self-harm, the refusal to look reality in the eye on almost everything that matters – but it’s this strange and deeply uncharacteristic policing of speech that most clearly reveals a country no longer in its right mind.

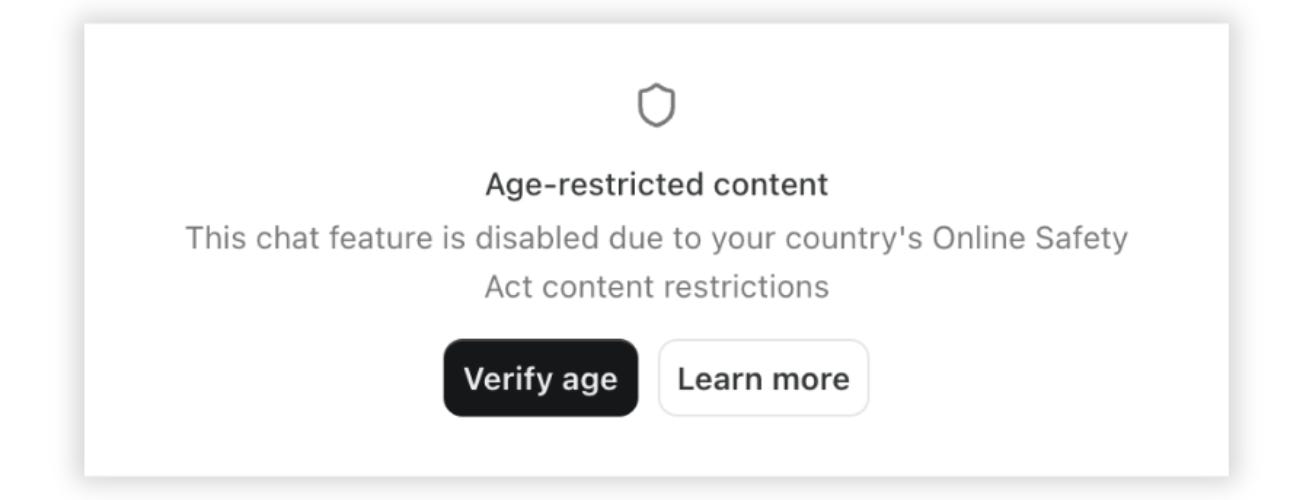

I feel it keenly because I write articles on controversial topics ranging from trans ideology to the rise of Islamism. I say things like “men cannot get pregnant” and “some cultures are better than others”. This week, Substack informed me I need to scan my face to keep using its chat feature, in compliance with Britain’s new Online Safety Act. It’s a small pop-up box, but it brought that knock on the door a little closer.

Describing reality now carries the risk of serious reputational harm and even legal prosecution. The UK government put it explicitly in a chilling tweet, which simply read: “Think before you post”. This is what Orwell meant by thoughtcrime, except Big Brother is now someone called Darren who works in the Metropolitan Police’s non-crime hate incident (NCHI) department.

This creeping authoritarianism is working. We see it in the normalisation of self-censorship – that little alarm bell in the corner of the mind, poised to go off when we wander into controversial territory. It’s in the moment you hesitate over a phrase or delete a sentence because you’re not sure where the invisible lines are any more. Most of us will never see a police officer about a Facebook post, but many of us are becoming attuned to the idea of wrongthink in our own minds.

In Areopagitica (1644), Milton argued that truth didn’t need protection from error; it needed freedom to contend with falsehood:

“Though all winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licensing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and falsehood grapple, who ever knew truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter”.

This was the principle, later developed by John Stuart Mill, that Britain gave the world. Trust free people to hear arguments and judge for themselves. Let truth emerge from the free and open exchange of ideas.

That was a nice idea while it lasted.